More than eight months after Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced he would place new limits on the use of solitary confinement in New York’s prisons, the regulations he said would be implemented still aren’t in effect.

Those limits were part of a deal Cuomo made last year with Democrats in the Legislature in place of a bill that would have placed strict limits on the sanction in New York.

That legislation, Cuomo said at the time, would have cost the state more than $350 million to implement. Local governments would have also been on the hook, Cuomo said. Supporters of the legislation have refuted those claims, saying the cost would be lower.

Cuomo and Democrats agreed to reject the bill, and instead allow the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision to promulgate a series of regulations intended to limit the use of solitary confinement and prevent certain practices.

The regulations were first proposed by the agency in August, after Cuomo and lawmakers committed to the plan in June. They were scheduled for a 60-day comment period before they were set to be finalized and implemented.

But, as of this week, they haven’t taken effect in full. Comments are still being considered before a finalized version is published and allowed to take effect.

When asked why the regulations hadn’t yet taken effect, a spokesman for DOCCS referred New York NOW to comments made by Acting Commissioner Anthony Annucci in February. Annucci was testifying before the Legislature at a hearing on the state budget.

Annucci said that, while the rules are being finalized, DOCCS is using $69 million in funding to begin infrastructure upgrades that will be required under the regulation. Those include new units that will be used to provide out-of-cell rehabilitative programming to individuals.

“DOCCS issued regulations for public comment that are currently under review,” Annucci said. “When fully implemented, these reforms will restrict the use of segregation for vulnerable populations, cap the amount of time someone can spend in segregation, and expand the number of specialized units available for individuals leaving segregated confinement.”

The rules were intended to set stricter limits on who’s eligible for solitary confinement, and under which conditions.

Pregnant women, or women within eight weeks of giving birth, would not be eligible for solitary confinement. Incarcerated individuals with a mental or physical disability, or a serious mental illness, would also be barred from the sanction, the rules proposed in August said.

The regulations would also, among other things, place a 30-day cap on the number of days someone’s allowed to be held in solitary confinement. That cap, under the rule would be phased in over the next few years and take effect Oct. 1, 2022.

There is currently no legal cap on the number of days someone can spend in solitary confinement in New York.

The use of solitary confinement would also be limited, according to the rule. It would only be allowed if an incarcerated individual’s behavior violates an institutional rule, or poses an “unreasonable risk” to the health or safety of staff or other inmates, the rule said.

Staff at prisons also wouldn’t be allowed to change the diet of someone in solitary confinement as a form of punishment, or any other reason, according to the rule.

It’s unclear when the rules will be finalized. Agencies, technically, don’t have a hard deadline on when they have to finalize a rule after it’s been proposed and opened for public comment. The process is arduous, and it’s not unusual for a regulation to sit idle for several months.

The regulations were intended to be implemented in place of a bill called the Human Alternatives to Long-Term Solitary Confinement Act, or HALT Act.

The legislation is an anomaly in the state Legislature. More than half of lawmakers in both the State Senate and Assembly have signed on to sponsor the bill, but it hasn’t come to the floor for a vote. That means the legislation would pass, but it hasn’t been moved.

Sources said, last year, that Democrats didn’t want to move the bill because they thought Cuomo would veto it, and the Senate didn’t have the votes to override a veto. That means the bill would ultimately fail, regardless of how many lawmakers rallied for it.

Cuomo was concerned about the cost, particularly because the legislation wasn’t dealt with in the context of the state budget, which is due in March. Lawmakers were considering passing the bill in June, which would have pushed the conversation around funding to this year.

The HALT Act would cap the number of days individuals can spend in solitary confinement at 15 days. It also includes a provision that would prevent individuals from being thrown back into solitary confinement immediately after they’re released.

Advocates have argued that the regulations proposed by DOCCS would allow correction officers to cycle inmates through solitary confinement, meaning they could remove them at the 30-day cap, but then throw them back in for another 30 days immediately after.

It’s unclear if that will be allowed under the final regulation — no one will know until it’s finalized, and it’s possible that DOCCS is tweaking the regulation based on comments from stakeholders.

The HALT Act would also allow, among other things, six hours of out-of-cell programming each day, and create a mechanism for individuals to be considered for early release from prison or jail, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union.

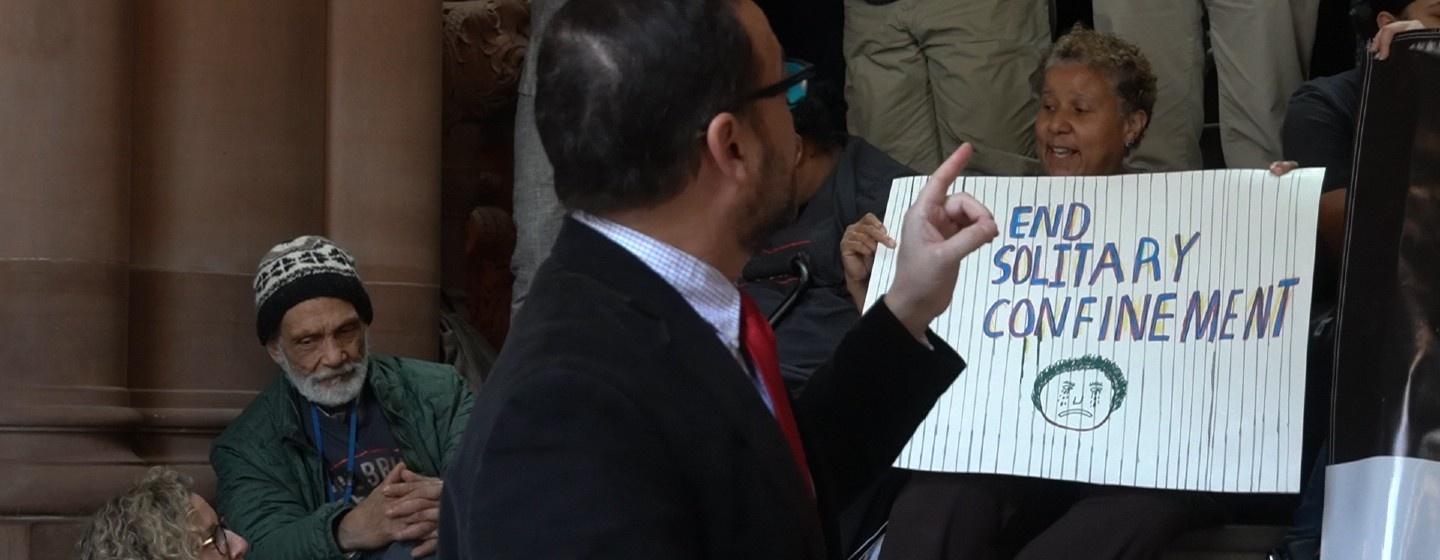

Advocates who support the bill have called on Democrats to pass it this year, though Cuomo hasn’t publicly changed his position on the legislation. Scott Paltrowitz, an advocate with the HALT Solitary Coalition, said lawmakers should approve it anyway.

“They need to act to end this torture because thousands of people are being tortured and they have the power to stop it,” Paltrowitz said. “There’s no excuse. It has to be brought to a vote.”

The New York State Correctional Officers and Police Benevolent Association is against the legislation, saying broad changes to solitary confinement would compromise the safety of staff in prisons, as well as other inmates.

It’s a tough year for lawmakers to consider any legislation that would mean more spending for the state, even if there’s a dispute on how much the changes would cost. Cuomo and Democrats who support the bill have disagreed on how costly the bill would be.

New York state started the year with a projected $6.1 billion deficit, and Cuomo has called the financial implications of the novel coronavirus pane “incalculable.”

Watch the full interview with Scott Paltrowitz and Victor Pate from the HALT Solitary Coalition: