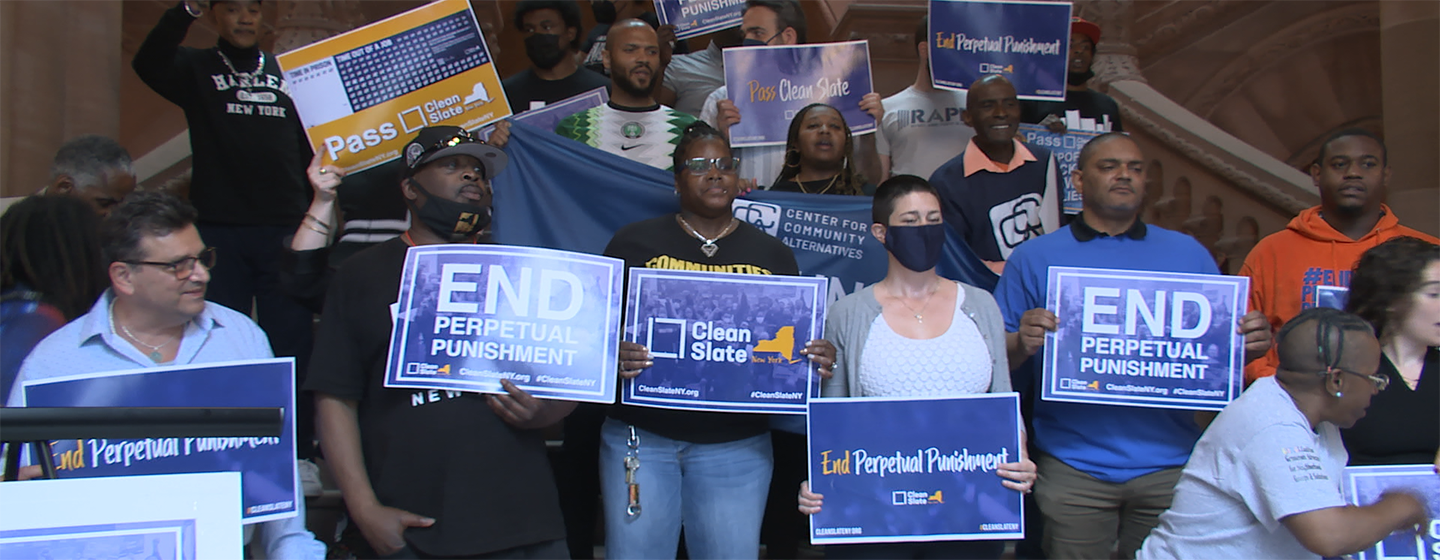

Clean Slate Act Passes State Senate, Assembly Fate Unclear

Clean Slate Act Passes the Senate, Assembly Fate Unclear

A proposed law in New York that would allow most conviction records to be automatically sealed after a waiting period passed the State Senate on Wednesday, but its future in the Assembly is less clear.

A handful of Democrats voted against the measure, but it passed with strong support from that side of the aisle. Republicans were opposed to the bill.

“This is a restorative bill. It’s about rehabilitation, it’s about our communities. It’s about investing,” said State Sen. Zellnor Myrie, D-Brooklyn, who sponsors the bill.

The Clean Slate Act, as it’s known, had garnered support in the Senate in recent weeks, but didn’t have the votes to pass the Assembly on Wednesday.

Assm. Catalina Cruz, a Democrat from Queens who carries the bill in the Assembly, said it wasn’t off the table, but that there wasn’t enough support to bring the measure to the floor.

“We have made some significant amendments to address concerns folks had,” Cruz said. “I’m hoping in the next 24 hours, we’re going to see our colleagues push in the same way we are pushing.”

The bill has had a turbulent experience in the state Legislature in recent years. Lawmakers claimed to have the votes to approve it last year, but blamed its failure to pass on a technical issue.

When lawmakers returned to Albany for this year’s legislative session, the bill found new life after Gov. Kathy Hochul announced her support for the measure in January.

Since then, lawmakers have gone through months of negotiations in hopes of striking a deal. That didn’t appear imminent Wednesday, but Assm. Latrice Walker, D-Brooklyn, said those conversations were ongoing.

“We look forward to having real conversations with all the individuals who believe that these are just policy, political, and anecdotal conversations,” Walker said. “I will continue to work with our colleagues, and speak to our conference, in order to get it done.”

The bill would create a procedure for most conviction records in New York to be automatically sealed after someone serves their sentence, and avoids another criminal charge during a mandatory waiting period.

It’s intended to help individuals who’ve struggled to find a permanent job, housing, or both, because of their criminal record. Potential employers and landlords can reject someone, in most cases, based on their conviction history.

The person would have to serve their entire sentence, including probation, to be eligible.

The amount of time they would have to wait to qualify after their sentence ends would depend on the level of charge on which they were convicted.

Traffic infractions and violations would be eligible for automatic sealing three years after the end of their sentence. Convictions for misdemeanors would be eligible for automatic sealing after three years as well, but felony convictions would have to wait seven years.

Sex offenses would not be eligible for sealing, and law enforcement agencies would still have access to the sealed criminal records.

Opponents of the bill have said they’re concerned that potential employers wouldn’t be able to see the sealed convictions on a background check. Senate Republican Leader Rob Ortt, R-Niagara, said it was part of a larger pattern of policies out of Albany related to criminal justice.

“Law-abiding citizens are concerned with crime. Innocent victims are under attack,” Ortt said. “Yet Albany is once again rewarding criminals and punishing victims. It’s absurd and abhorrent.”

Lawmakers were expected to end this year’s legislative session on Thursday.

Related

New Yorkers with older convictions could have records sealed with the Clean Slate Act.

This bill looks to clear individuals' criminal history after they've served their sentence